How did music mirror the features of art and architecture during the Romantic Period?

The emergence of Romanticism in the 19th century came in response to radical changes in the social, political, and cultural climate. Artists sought liberation from the rigid social conventions and restraint of the Classical era, nostalgia for rural life after the Industrial Revolution, and pride for their national and individual identities following the Napoleonic Wars. Many parallels can be drawn between the features of differing art forms during the period due to their shared context, as well as the mutual influence they had on each other.

Nostalgia was a central theme in 19th century art, expressed as a longing for an idealised past and reaction against the rapid changes of the modern world. Artists pursued ‘neo-Medievalism’ as a reactionary ‘antidote to the ills of the Industrial Revolution’ (Dorfman, 2020). For example, the Arts and Craft movement rose in opposition to the negative creative and societal impact of ‘soulless machine-made production’ (Singh, 2022). The Pre-Raphaelites rejected the unimaginative and artificial style of academic artistic practice, in pursuit of ‘physical and psychological realism’ (Tate, n.d). They revived old stylistic tendencies like fresco painting whilst innovating new techniques to produce intensely saturated colours and meticulous background detail (Gray, 2006). Through portrayal of ‘subject matter of a noble, religious, or moralising nature,’ they sought to advocate artistic renewal and moral reform (Meagher, 2004).

A.W. Pugin, in his 1836 publication Contrasts, similarly criticised new industrialised methods of production as ‘devoid of soul, sentiment, or feeling,’ advocating that monuments from the Middle Ages were both aesthetically and morally superior to the ‘superficial style’ and ‘present decay of taste’ of Classical architecture (Pugin, 1836, p30). This prompted a resurgence in medieval architectural designs, known as the Gothic Revival. Ornate interiors, grand and complex shapes, and asymmetry juxtaposed the order, proportion, and uniformity of Classical style. Music followed a similar direction of authenticity and stylistic liberation; however, Classical forms were maintained rather than rejected, laying the foundation for expansive, dramatic expression by stretching the boundaries of traditional forms and harmonic language.

A notable example of this can be seen in Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, comprising of five movements (instead of the customary four). Berlioz used many Romantic stylistic traits such as extreme dynamic ranges, chromatic harmony, imbalanced phrases, and most notably, a larger orchestra exploring experimental timbres (opposed to the set instrumental roles of the Classical period), to achieve richer, more expressive sounds. Berlioz advocated for the expansion of the Romantic symphonic orchestra in his Treatise on Instrumentation and Orchestration, arguing that small orchestras ‘have so little impact, and are consequently of little value’ (Berlioz, 1844). The dramatic expansion in orchestral size during the period had practical implications on the architecture of concert halls, which needed to accommodate larger orchestras and audiences. This in turn affected the acoustics, requiring consideration of how sounds would blend to achieve desired tonal colours (Herr and Siebein, 1998).

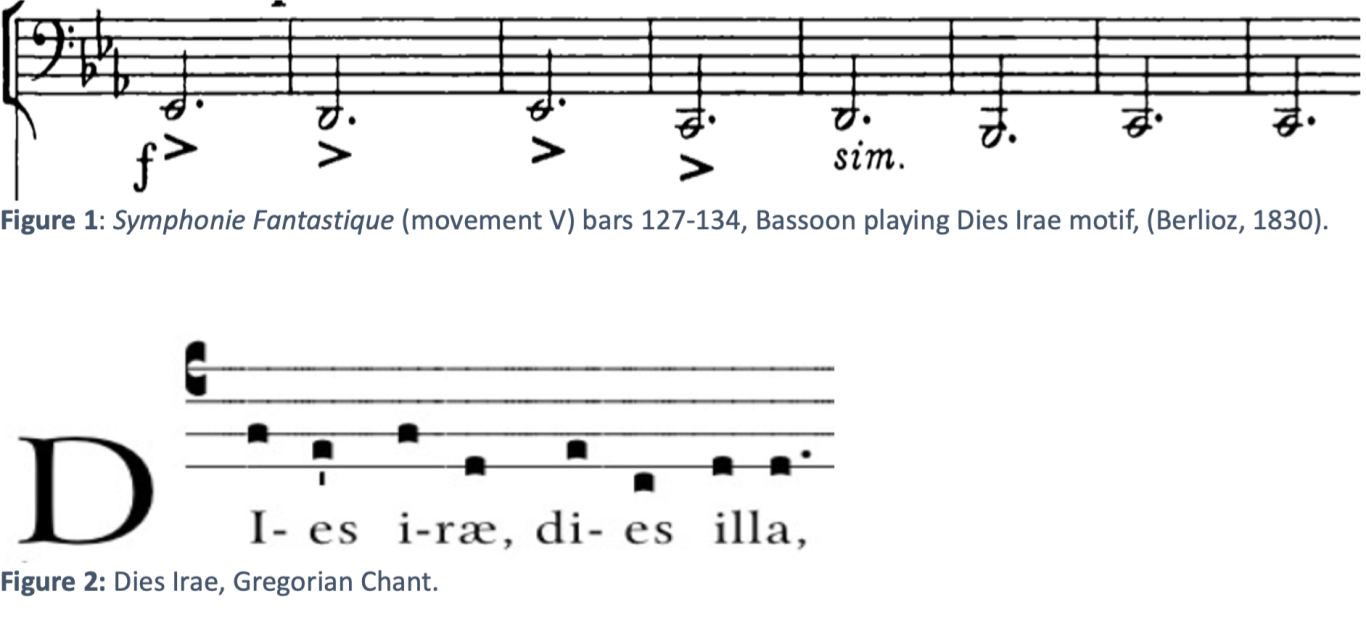

The historic aesthetic of the Gothic Revival inspired a new genre of Gothic literature. Stoker’s Dracula for instance, refers to architectural features such as ‘great round arches’ and ‘high walls, of ancient structure, built of heavy stones’ (Stoker, 1897). Dark tropes like the supernatural, villainy, emotional distress, and madness reflected contemporary political themes central to Romantic ideology; these include fear of scientific advancement in Shelley’s Frankenstein, consequences of a repressed society in Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde, and criticism of social and gender inequality in Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Romantic composers often explored dark subject matter in their symphonies through similar means of medieval reference; the ‘visions of suicide and murder, ecstasy and despair’ in Symphonie Fantastique (Thomas, 2011) are evident in the 5th movement (figure 1) through use of the Dies Irae motif (figure 2) from the 13th century Gregorian requiem chant.

Gothic literature also had direct influence on programmatic Symphonic writing due to the ‘quintessential Romantic concern with the literary potential of musical expression’ (Bodley, 2017, p18). Goethe’s 1829 play Faust was reimagined by composers including Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Berlioz, and Liszt. The popularisation of this subject matter aligned with the Romantic inclination to engage with ‘contemporary intellectual concepts’ like the complex moral nature of mankind, through the lens of a narrative from the Middle Ages (Bodley, 2017).

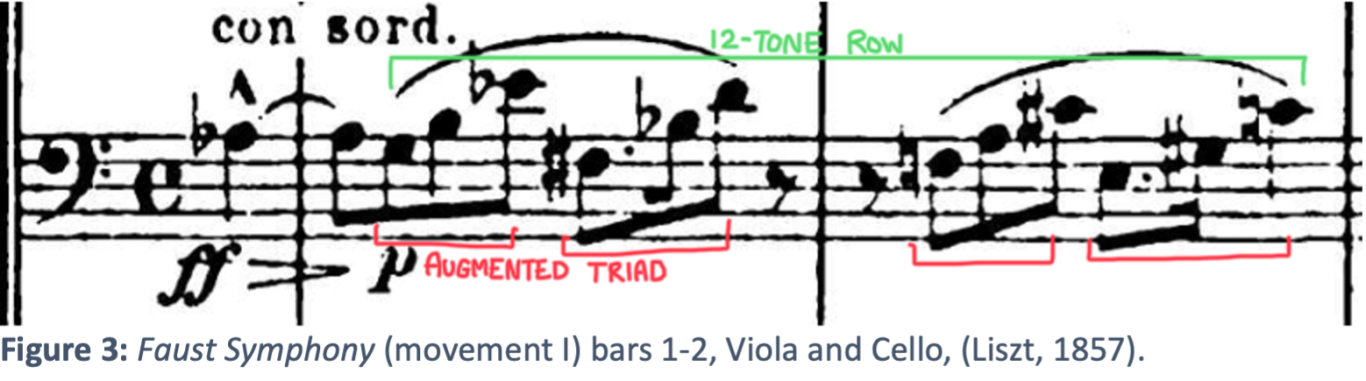

Liszt’s Faust Symphony exemplifies the prioritisation of narrative to the structure of programmatic writing, centring each of the three movements around a different character. The first is in sonata form but transformations of the motifs align primarily with the narrative rather than strictly adhering to exposition, development, and recapitulation of themes (Longyear and Covington, 1986). The first motif (figure 3), constructed from a descending sequence of augmented triads, captures the complex morality of Faust’s personality through an ambiguous assertion of tonality, conveying frustration and unfulfillment with the absence of harmonic resolution. Chromaticism was often employed in 19th Century music to heighten feelings of tension, but Liszt’s use of ‘the earliest conscious twelve-tone row’ also serves a narrative function as a ‘representation of all the elements in the universe,’ symbolic of Goethe’s theme of Macrocosm (Wei, 2016, p7).

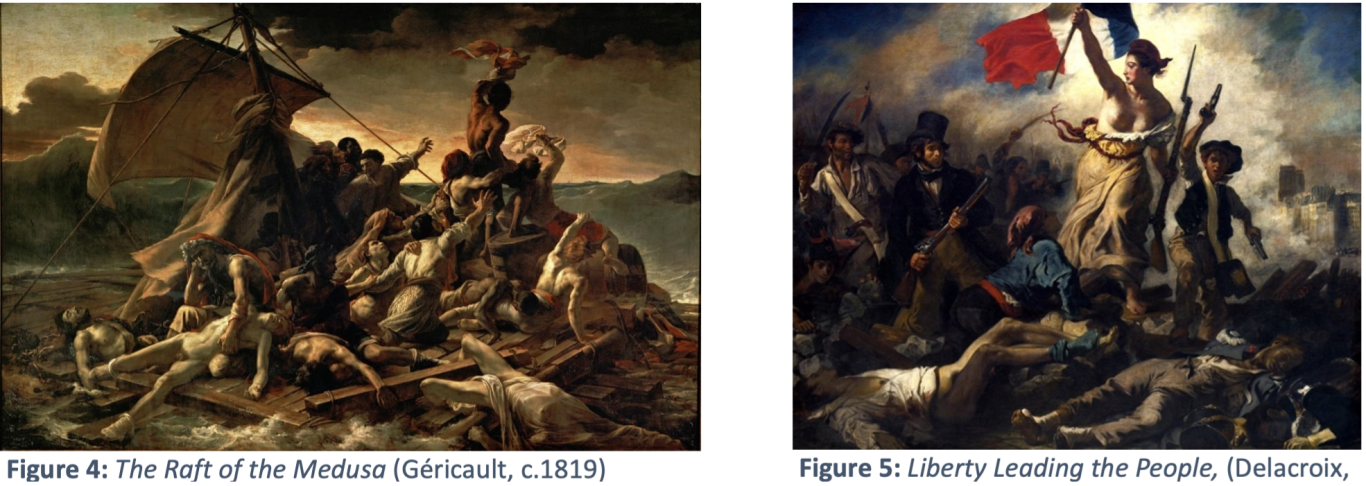

The artistic trend of medieval stylistic reference was also a consequence of widespread nationalism across Europe. ‘Escalating international tensions […] fuelled the need to nationalize the masses in order to overcome internal discord and stimulate national unity’ (Storm, 2009, p3). Movements like the Gothic Revival were an attempt to resurrect ‘communal memory in a fractured society’ by using design features that reference the country’s unified past (Trask, 2018, p51). Visual artists similarly portrayed themes from their nations’ history; Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa was both praised and criticised for its ‘bold and frank depiction of the real state of affairs in France,’ and Delacroix’s symbolism of the French Republic gave hope for ‘liberty, equality, and fraternity’ following the Revolution (Maksimova, 2023).

Another basis of national unity came from folklore in celebration of the ‘cultural prestige’ of a nation’s shared heritage (Norberg, 2022, p101). In 1812, the Brothers Grimm published a collection of traditional German folk tales to replace the ‘artificial’ modern literature they felt was incapable of expressing ‘genuine essence of Volk culture that emanated naturally from experience and bound the people together’ (Zipes, 2015). Composers similarly embraced folk influences, creating pieces that were regarded as representative of their nation, partly owed to how they were received and recontextualised; national schools of music were established to teach ‘elite compositional tradition’ and promote a country’s distinct individual musical identity (Gelbart, 2021). However, the subject matter and material used by composers was often a personal reflection of their identities and national pride.

Chopin for instance, ‘elevated the mazurka from just a peasant dance to a national sound in ethnic traditional music’ (Cintron, 2014, p19) by fusing traditional Polish folk elements with contemporary tonal language. He used triple meter, accenting the second or third beats in reference to peasants’ foot stomping, and explored ‘modally inflected melodies’ (Yip, 2010). The Lydian mode, indicated by a raised fourth, is observed in many of Chopin’s mazurkas, functioning stylistically as chromatic tonal expression, and structurally as a leading tone to the dominant (Viljoen, 2000). These works were explicit references to the composer’s homeland, but subtle influences from different nations’ cultures also found their way across Romantic writing, often in the form of admiration of the natural world.

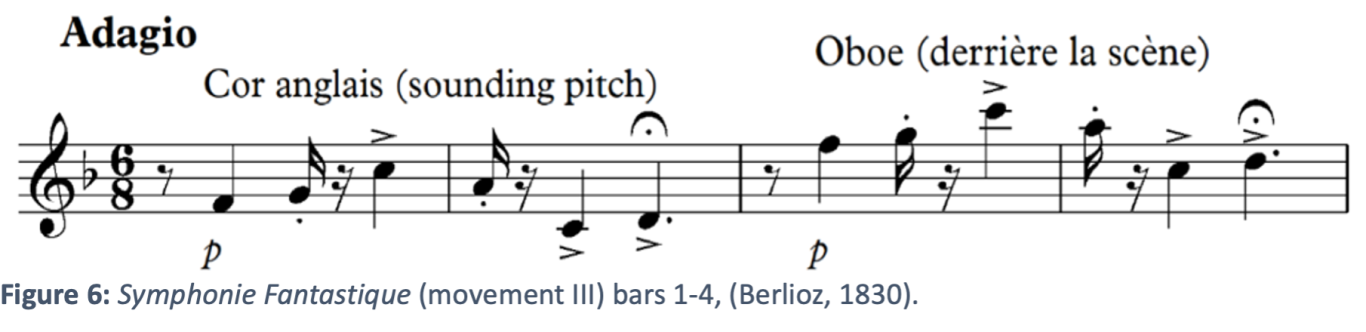

The third movement of Symphonie Fantastique depicts a countryside landscape, opening with an ‘extensive series of alphorn-evocative motifs,’ inspired by the music of the herdsmen in the Chartreuse mountains (Jones, 2022, p5). The tonality and shape of the motif (figure 6) is evocative of the alphorn’s natural harmonic series, and short phrases ending on paused notes replicate the horn players’ breathing pattern. A scenic distant echo is also painted through the dialogue between cor anglais and oboe; Berlioz discusses the pastoral qualities of this dialogue in his Treatise on Instrumentation and Orchestration, stating the cor anglais is the superior instrument for ‘reviving images and feelings from the past’ (Berlioz, 1844).

The principles and values of the Romantic period bound together the diverse artistic landscape of the 19th century. Besides instances where art was directly inspired by existing works, such as symphonic takes on Goethe’s Faust, the most evident correlation between features of music and art are in their shared ideology. Artists explored similar subject matter (like national pride, social liberation, and authentic expression), with equivalent methods of depiction (like medieval and cultural references, rejection of previous academic principles, and explorative techniques). This ‘often explicit attempt to represent every shade of human emotion’ (Kluball and Kramer, 2015, p161), resulted in the diverse, but ideologically unified aesthetic of Romanticism.

REFERENCE LIST:

Anon (n.d.). Dies Irae | Gregorian Chant Hymns. [online] gregorian-chant-hymns.com. Available at: https://gregorian-chant-hymns.com/hymns-2/dies-ire.html.

Berlioz, H. (1844). A Treatise Upon Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration.

Berlioz, H. (1971). Temperley, N. (ed) Symphonie Fantastique, Kassel: Bärenreiter.

Bodley, L.B. (2017). Music in Goethe’s Faust : Goethe’s Faust in music. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press.

Cintron, P. (2014). Analysis of Chopin’s Mazurkas and its Influence on Polish Cultural Nationalism . [online] Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1332&context=masters [Accessed 21 May 2020].

Dorfman, J. (2020). Medieval Revival. [online] Art & Antiques Magazine. Available at: https://www.artandantiquesmag.com/victorian-radicals/.

Gelbart, M. (2021). The Cambridge companion to music and romanticism. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp.74–91.

Gray, C. (2006). Subversive Nostalgia and Pastoral Utopia: William Morris. [online] victorianweb.org. Available at: https://victorianweb.org/painting/prb/gray.html.

Herr, C. and Siebein, G. (1998). An Acoustical History of Theatres and Concert Halls: An Investigation of Parallel Developments in Music, Performance Spaces, and the Orchestra MUSIC AND ARCHITECTURE THROUGH THE AGES. [online] Available at: https://www.acsa-arch.org/proceedings/Annual%20Meeting%20Proceedings/ACSA.AM.86/ACSA.AM.86.29.pdf.

Jones, F. (2022). Berlioz Society Bulletin: Berlioz and the Alphorn. [online] pp.22–30. Available at: https://www.amazingalphorn.co.uk/PDFs/AlphornArticles/Frances-Jones-Berlioz-and-the-Alphorn.pdf.

Kluball, J. and Kramer, E. (2015). Understanding Music: Past and Present. [online] Dahlonega, Georgia: University of North Georgia Press, pp.160–224. Available at: https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=arts-textbooks.

Liszt, F. (1917). A Faust Symphony, Leipzig: Breitkopf and Härtel.

Longyear, R.M. and Covington, K.R. (1986). Tonal and Harmonic Structures in Liszt’s Faust Symphony. Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 28(1/4), p.153. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/902417.

Maksimova, A. (2023). The most famous Romanticism paintings you need to know • Art de Vivre. [online] artdevivre.com. Available at: https://artdevivre.com/articles/the-most-famous-romanticism-paintings-you-need-to-know/.

Meagher, J. (2004). The Pre-Raphaelites. [online] Metmuseum.org. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/praf/hd_praf.htm.

Norberg, J. (2022). The Brothers Grimm and the Making of German Nationalism. Cambridge University Press.

Pugin, A.W. (1836). Contrasts. Wiltshire: Alderbury.

Singh, S. (2022). How the Arts and Crafts Movement Rebelled Against the Machine Age. [online] Owlcation. Available at: https://owlcation.com/humanities/How-The-Arts-and-Crafts-Movement-Reacted-Against-the-Machine-Age.

Stoker, B. (1897). Dracula. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Storm, H.J. (2009). Painting Regional Identities: Nationalism in the Arts, France, Germany and Spain, 1890—1914. European History Quarterly, 39(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265691409342651.

Tate (n.d.). Were the Pre-Raphaelites Britain’s First Modern artists? – Essay. [online] Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/pre-raphaelite/were-pre-raphaelites-britains-first-modern-artists.

Thomas, M.T. (2011). Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique: Keeping Score | PBS. [online] Pbs.org. Available at: https://www.pbs.org/keepingscore/berlioz-symphonie-fantastique.html.

Trask, J.E. (2018). The Historicist Requirement for the New Houses of Parliament: Gothic Revival as National Identity in 1830s Britain. doi:https://doi.org/10.18130/V3W08WG3W.

Viljoen, N. (2000). The Raised Fourth Degree of the Scale in Chopin’s Mazurkas. Acta Academia. [online] Available at: https://scholar.ufs.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/02af74a2-89f1-4ae9-86cc-567fecfc3fc8/content#:~:text=1%20There%20are%20only%20two,the%20Lydian%20and%20Phrygian%20modes.

Wei, M. (2016). Goethe’s Faust and Nineteenth Century Music: Liszt’s Faust Symphony. Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects. [online] Available at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1031&context=senproj_f2016.

Yip, S.Y.J. (2010). Tonal and Formal Aspects of Selected Mazurkas of Chopin: a Schenkerian View. [online] Available at: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/77777/yips_1.pdf?sequence=3.

Zipes, J. (2015). How the Grimm Brothers Saved the Fairy Tale. [online] The National Endowment for the Humanities. Available at: https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2015/marchapril/feature/how-the-grimm-brothers-saved-the-fairy-tale#:~:text=In%201808%2C%20their%20friend%2C%20the.